9 Cucumber Growing Tips to Try This Season

Cucumbers, sliced or pickled, are favorites fresh from the summer garden and the easygoing vines and prolific producers. A few benchmarks of cucumber care promote the best yields and overall vigor. Gardening expert Katherine Rowe highlights top tips for enjoying outstanding cucumbers right off the stem.

Contents

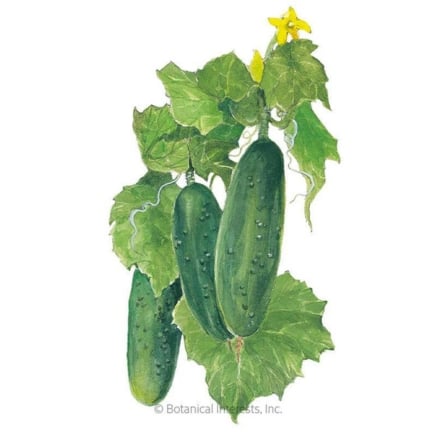

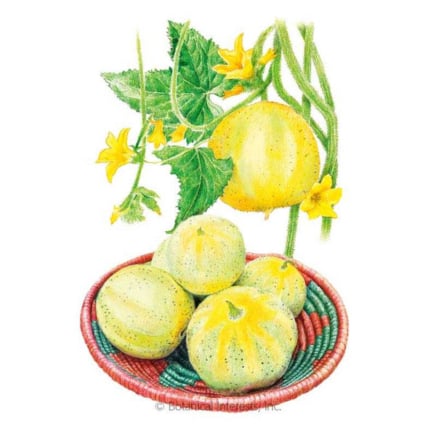

From heirlooms to modern space-saving hybrids, pickling to slicers, cucumbers are a crisp, hydrating delight in the summer garden. The easy-to-grow vining crop yields multiple fruits per plant, whether climbing and sprawling or a short, bushy type. It doesn’t take many plants to enjoy a bounty.

Because of their versatility and ease in the edible landscape and on the plate, Cucumis sativus are a favorite to grow from seed as temperatures warm in early spring. With a few care tips for the best health and to maximize the refreshing harvest, cucumbers show the vigor, performance, and refreshing crunch we look forward to each summer.

Avoid Transplant Disturbance

The first tip for healthy cucumbers is to establish vigorous seedlings. They develop extensive roots that are sensitive to disturbance at transplanting, and direct sowing is the best way to minimize disruption. Sowing them in their permanent location poses the least risk and stress on the new sprout.

You can start seeds indoors a few weeks before the final frost, but the tender roots are best suited for biodegradable pots or soil blocks. Keep them indoors for only a short time to minimize taproot development, which lessens disturbance when planting them in the ground, raised beds, or containers. Otherwise, wait until two weeks after the frost or when soil temps are at least 60°F (16°C), or ideally 70°F (21°C) or above to direct sow.

Take care when weeding to avoid digging into roots as the vines establish. Their lateral roots are close to the soil surface. Lightly cultivate weed seedlings as they pop up to get rid of them. Weeding reduces competition for sunlight, moisture, and soil nutrients.

Wait for Warmth

Cucumbers flourish in warm conditions, and it’s a worthwhile tip to wait for the right temperatures instead of rushing the planting in spring. Seeds need warm soil to germinate, and seedlings in chilly conditions may be slow to develop. Even a light frost kills these heat-loving vines.

Let soil temperatures rise above 60°F (16°C) before planting. The warmer, the better for cucumbers, with the ideal range between 70-90°F (21-32°C). Long summer days and warm nights promote vigorous roots and vines. Grow them in full sun, with at least six hours daily.

Go Vertical to Maximize Space

Growing cucumbers vertically saves space and allows straight, shapely fruits to develop. With vertical interest and added dimension, it’s fun to see the fruits develop as they suspend from the vine (harvesting is easy, too). Use a five to six-foot trellis with sturdy crosswires for training and tying.

There are a number of rewards to growing cucumbers on trellises, A-frames, or arches to maximize the harvest. They include:

Saving space: Growing upward allows the otherwise-sprawling vines to grow in versatile garden situations, from small sites like balconies, courtyards, and patios to raised beds and containers. It makes room in the bed for other selections.

Improving airflow: Lifting the vines improves air circulation. As leaves and fruits are off the ground, conditions are less damp and crowded, helping to stave off fungal problems like powdery mildew at bay. With less irrigation splashing on leaves and a faster dry time, conditions for fungal disease are less optimal.

Pest and disease scouting: With vertical specimens, spotting pests and diseases is easier. Inspect regularly for mildewed leaves and snip them off. Insects like the cucumber beetle and squash vine borer may be easier to detect on open-air growers, as there are fewer hiding places.

Sun exposure: All-over light exposure improves with vertical supports. Not only is sunlight essential for photosynthesis, it’s also necessary for fruits to develop healthy skins.

Dwarf cucumber varieties save space and don’t need staking. Depending on the selection, they produce full-sized cukes in sizeable yields on compact vines.

‘Spacemaster 80’ is delicious at full size for slicing or small for pickling. It doesn’t take up much growing room with short, two to three-foot vines. ‘Quick Snack’ produces small fruits in six to eight-inch pots. Grow them indoors or out by sowing them directly in the full-sized pots.

Prune for the Best Yield

While bushy types don’t need much pruning, vining types benefit from simple, strategic trimming to manage growth and direct energy. Pruning cucumbers involves pinching the growth tips (the suckers the emerge that emerge from nodes along the main stem. By removing rambling offshoots close to the main vine, we encourage more female flower production (leading to more fruits).

Remove the growth points when young plants are less than three feet tall to direct growth. After that, let them develop if you’ve got space or, if growing vertically, remove some continually to improve air circulation.

It also benefits the future harvest to remove the lower blossoms on the initial two to three feet of the stem. Removing the lowest ones allows energy to go toward stem and foliar development, then into flowering and fruiting (producing more blossoms).

Remove discolored or diseased foliage anytime, particularly as lower leaves age.

Boost Pollination

Sometimes, vines flower and produce odd-looking or poorly shaped fruit, often due to poor pollination. The cucurbits produce male and female flowers on a single plant. They depend on insects for pollination, and unpollinated female flowers produce underdeveloped fruits.

To boost pollination, grow flowering plants nearby to attract bees and other beneficial insects. Nectar and pollen-rich blooming herbs, perennials, and annuals draw traveling pollinators who visit the male and female blossoms. To ensure pollination, hand-pollinating using a toothbrush or paintbrush distributes pollen granules between the blooms. Newer varieties (usually seedless) are self-fruitful and don’t rely on pollination between male and female flowers.

With all the extra bed space gained in going vertical, consider growing companion plants for cucumbers. These beneficial partners require the same growing conditions and deter pests naturally.

Nasturtiums and marigolds are annuals with pest-deterring qualities. Perennials like beebalm and catmint make aromatic additions that pests find distasteful. These companions also bring plenty of blooms, drawing pollinators and increasing biodiversity. Plant the bloomers all around the cucurbits.

Don’t Overfertilize

Insufficient sunlight, too-cool temperatures, or overfertilizing can lead to a lack of flowering and fruiting. Too much nitrogen produces leafy stems but reduces flowering. The plant directs energy into foliage and vine growth rather than fruit production.

At planting, amend the soil with compost or other organic matter to ensure it’s organically rich. Cucurbits prefer a sandy loam and need well-drained soils to thrive.

As seedlings grow, fish emulsion or other low-grade organic fertilizers give a boost of needed nitrogen for leafy growth. As they get taller, switch to a fertilizer higher in phosphorus (the K in the N-P-K fertilizer ratio) to promote budding and flowering. Or use a formula tailored to vegetables. A 5-10-10 is a general all-purpose ratio for veggies.

Phosphorous and potassium are necessary for flowering and fruiting. While nitrogen is needed early on as plants establish, an overage is too much of a good thing. Avoid applying excess nitrogen through manure and compost during the growing season.

Watering Correctly

Consistent moisture is essential throughout the growing season. One to two inches a week, including rainfall and irrigation, is usually sufficient. Fluctuations in water cause stress, leading to halted growth. To ensure good drainage, mound soil prior to planting or opt for raised beds.

If you notice a rotting patch at the base of a ripening cuke, it’s likely blossom end rot. In the same way it affects tomatoes, a cucumber looks perfectly healthy until suddenly beginning to rot.

Blossom end rot likely occurs from water fluctuations—extreme moisture and dryness cause a lack of nutrient uptake, including calcium. At planting, scatter bone meal to promote calcium availability and keep moisture consistent.

Soil pH is another factor in calcium absorption. Soils with a low pH or high pH may inhibit availability. In the fall, amend with garden lime or sulfur, depending on a soil test, to reach slightly acidic soils for cucumbers (around 6.0 to 6.5).

If you notice distinct yellow and brown spots, you may be dealing with anthracnose, a common leaf blight. Fuzzy, powdery spores on the undersides of leaves and yellow upper speckling indicate powdery mildew or downy mildew. A horticultural oil like neem can stave off early infections.

Provide plenty of air circulation around vines to prevent damp conditions, and avoid splashing the leaves through irrigation when feasible. Water at the ground level through drip irrigation or soaker hoses to avoid overly wet conditions and spreading the spores through splashing water. Disinfect tools after pruning to avoid moving spores from plant to plant.

The Value of Mulch

A layer of mulch, like clean straw or compost, helps regulate soil temperatures, retain moisture, and suppress weeds. To allow the sun’s warmth to reach developing roots, wait to apply mulch until soil temperatures are above 75°F (24°C).

Of extra value of this cucumber mulching tip is its help in preventing stem access to cutworms and cucumber beetles. Cucumber beetle adults feed on leaves, blossoms, and fruits, while larvae feed on roots and stems. Among many cucurbits, they spread bacterial wilt. Regular scouting for each pest benefits the crop. Pyrethrin sprays help treat the squash bug and cucumber beetle.

Fusarium and Verticillium wilt are fungal diseases that cause wilting leaves, blackened leaves and stems, and plant decline. They spread from spores in the soil and can come with infected seeds or transplants. Wind, water, and garden tools also spread the spores. The fungus impacts the roots and affects nutrient and water uptake. With fungal wilts, you may see one half of the plant wilting more than the other.

Unfortunately, there are no treatments for wilts. Remove and dispose of affected plants, keeping them out of the compost pile. Grow disease-resistant varieties to limit the spread.

Picking at Peak Harvest

A ripe cucumber means a crisp cucurbit that’s not too bitter or seedy. Look for a uniform shape with consistent dark green skin. Immature fruits may have ridges, spines, or bumps, which mellow as cucumbers develop. Cucumbers are best picked small to avoid bitterness in overly large ones.

In overripe cucumbers, the blossom end becomes streaked with yellow. Developed seeds lead to an acrid flavor. If your cucumber is bitter but not overripe, it may be due to heat or water stress. Increase water or mulch to help retain moisture and regulate temperatures.

The “days to maturity” indicator on the seed packet is a good guideline for gauging when to harvest or at least a time frame for checking. Cucumbers are usually ready in 50-70 days, depending on the variety.